Major Earl Hancock “Pete” Ellis, U.S. Marine Corps, strategist whose vision of forward bases and maritime sustainment shaped modern amphibious warfare.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, long before radar, satellites, or unmanned systems, a Marine Corps officer looked across the Pacific and saw a future war taking shape. Major Earl Hancock “Pete” Ellis, remembered most often for his influence on amphibious doctrine, was not captivated by islands themselves. His focus was on something more enduring: how maritime power is sustained, how it moves, and how it survives in the spaces between decisive battles.

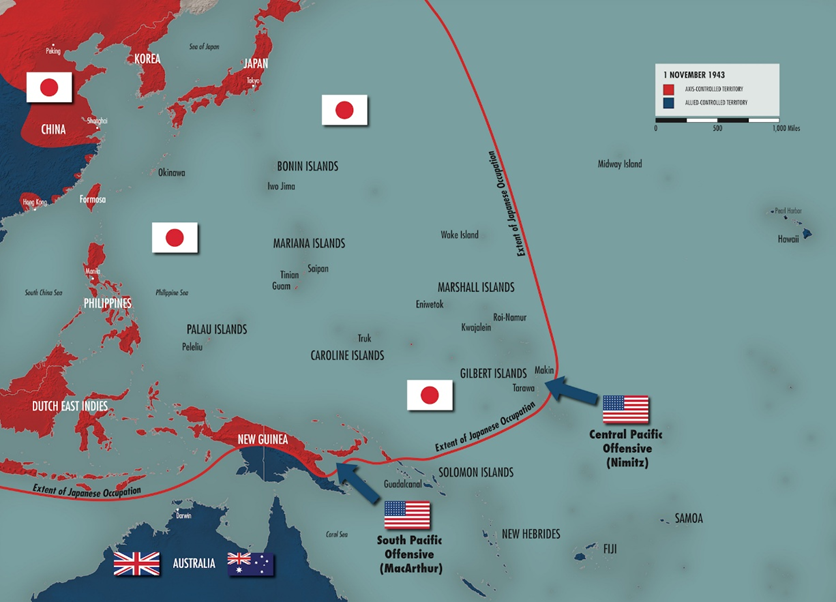

Ellis’s work begins from a simple premise: naval fleets do not operate in isolation. Amphibious forces do not exist without ports, anchorages, logistics nodes, and forward bases that allow them to assemble, refit, and project power onward. His concept of what later became known as “island hopping” was not about conquest for its own sake. It was about control, control of maritime space through a network of defended positions that enabled maneuver while denying the same freedom to an adversary.

Ellis’s vision treated the Pacific as an interconnected system of bases and sea lines, not a series of objectives.

That insight remains as relevant today as it was a century ago.

The geography has changed, the technology has evolved, and the character of warfare has shifted, but the underlying logic of sea power has not. Modern expeditionary and amphibious forces still rely on a network of forward locations to operate effectively. We may now refer to them as expeditionary advanced bases, forward logistics sites, or partner ports, but they serve the same purpose Ellis identified: they are the foundations upon which maritime power rests.

Amphibious operations have always depended on secure access, logistics, and freedom of maneuver from the sea.

As Ellis, later posthumously promoted to lieutenant colonel, wrote “the system of advanced bases is the very backbone of naval power in the Pacific.” Islands mattered not as prizes, but as enablers; nodes that made sustained maritime operations possible.

The uncomfortable truth is that many of these foundations are far more vulnerable than our assumptions suggest.

For much of the post–Cold War era, the United States operated with the luxury of secure rear areas. Ports and shipyards were treated as administrative spaces rather than contested terrain. Maritime security, particularly in domestic or partner ports, was often framed as a compliance exercise instead of an operational necessity. That worldview is rapidly becoming obsolete. Recent conflicts and gray-zone maritime activity have already demonstrated how quickly ports and littoral infrastructure can become contested without ever crossing the threshold of open war.

Adversaries have watched how American power is projected and sustained, and they have drawn their own conclusions. Rather than confronting US forces head-on, they have invested in ways to disrupt logistics, harass forward positions, and exploit the seams between military, civilian, and commercial maritime activity. Ellis would have understood the logic immediately. As he warned a century ago, an adversary’s objective is often “to deny us the use of the sea by attacking our bases and our communications.” Low-cost unmanned systems and deniable methods are being employed not by accident, but because they target the ports, anchorages, and sustainment nodes on which maritime power depends.

This is where the conversation around unmanned surface vessels (USV) begins to matter, but also where it often goes wrong.

Much of the current discourse around USVs is dominated by offensive thinking. Manufacturers understandably showcase speed, range, payload, and lethality. Demonstrations emphasize striking targets, swarming adversaries, or collecting intelligence in denied environments. These capabilities are impressive and they have a place in modern naval operations, but when defensive employment is ignored, unmanned systems risk creating new escalation pathways rather than mitigating existing ones.

Defensive maritime security is not simply offense turned inward. It is a different mission entirely, governed by different constraints and judged by different measures of success. In ports, anchorages, and littoral approaches, the challenge is rarely about finding something to destroy. It is about understanding what is happening, deciding when something matters, and responding in a way that preserves freedom of action without triggering unintended escalation.

The distinction mirrors the assumptions that shaped Ellis’s planning. His planning assumed friction, uncertainty, and imperfect information. He understood that most decisions in war are made without clarity and under pressure, and that preserving command judgment is often more important than maximizing firepower.

Defensive USV employment lives squarely in that space. That is especially true in expeditionary environments, where maritime forces operate from austere, temporary, or partner locations with limited manpower and little margin for escalation error.

In a real-world maritime security environment, contacts are ambiguous. Fishing vessels, recreational craft, commercial traffic, and legitimate port activity coexist with potential threats. Rules of engagement are shaped by law, policy, and political consequence as much as by tactical necessity. The use of force is rarely binary, and mistakes are not only operationally costly but strategically damaging.

Autonomy does not eliminate these realities. If anything, it amplifies them.

This is why defensive autonomy in expeditionary maritime security is not, at its core, a technology problem; it is an integration problem. The question is not whether a USV can navigate, detect, or even engage. The question is how that capability fits into a broader system of human decision-making, escalation control, and mission assurance. Defensive USVs must extend awareness and presence while remaining subordinate to human judgment. They must buy time and space, not close decision loops prematurely.

At the same time, the pressure on human operators continues to grow. Amphibious and expeditionary units are expected to operate across wider areas with fewer people. Every sailor or Marine tasked with standing watch, patrolling a perimeter, or monitoring a sensor feed is one less focused on mission execution. Fatigue, distraction, and cognitive overload are not abstract concerns; they are daily realities in maritime operations.

Properly integrated USVs change that equation. Not by replacing people, but by allowing people to focus on what humans still do best: assess intent, manage escalation, and make judgment calls in complex environments. In this sense, unmanned systems are not a revolution so much as a restoration of balance. They allow manpower to be applied where it matters most, while maintaining persistent coverage of the spaces that enable operations. Where many efforts falter is in assuming that this integration happens naturally. It does not. Hardware alone does not solve defensive maritime security. Nor does simply adding sensors, autonomy, or connectivity to existing force protection models. Effective implementation requires an understanding of how maritime security actually works at the deckplate level, where legal authorities, operational requirements, and human judgment intersect.

This is the gap that remains largely unaddressed across the industry.

USV manufacturers build platforms. Traditional security providers supply personnel. Government programs produce requirements and acquisition pathways. Few organizations operate comfortably at the intersection of all three, and fewer still are willing to confront the hard questions of rules of engagement interpretation, escalation management, and real-world use-of-force decision-making in a maritime environment.

This is precisely where Six Maritime has focused its efforts.

What distinguishes defensive USV integration in expeditionary settings is not the platform, but the operator’s understanding of how maritime security actually fails and how to Six Maritime approaches unmanned systems not as a novelty or a sales pitch, but as an operational necessity shaped by experience. The company’s work in maritime security, inside ports, shipyards, and force protection zones, has made one reality clear: defensive USV integration cannot be theoretical. It must function under real rules, real scrutiny, and real consequences.

By designing unmanned integration around operational security requirements rather than abstract capability, Six Maritime is addressing the problem Ellis would recognize immediately: how to protect the infrastructure that makes sea power possible, without undermining the very principles that allow that power to be exercised responsiblyrevent those failures before they escalate. The measure of success is not whether a system works in isolation, but whether it reduces risk, preserves decision space, and prevents escalation in live maritime environments.

Marine Corps historian Joseph Alexander later noted that Ellis anticipated decisive actions would occur far from the main battle fleet, a view that resonates uncomfortably well in today’s contested maritime environment. Ellis planned for a war he believed was coming and history proved him right. Today’s challenge is different in form, but similar in substance. The United States continues to rely on maritime power to deter, project, and prevail. That power still depends on secure nodes, sustained access, and freedom of maneuver from the sea.

Ellis assumed that forward bases would be exposed, contested, and defended with limited resources. Modern expeditionary forces face the same reality, only now at greater scale and speed. Defensive unmanned surface vessels are no longer optional enhancements to that equation. They are becoming foundational. Implementing them correctly, within rules of engagement, alongside human operators, and in support of mission continuity rather than technological spectacle is the real challenge ahead.

As later naval thinkers would echo, sea power rests as much on access and sustainment as on decisive battle. Ellis understood that truth early and modern maritime security must now grapple with it directly. Ensuring that today’s amphibious and expeditionary forces can operate securely from the sea demands the same clarity of thought. Defensive USV integration is not about the future of warfare. It is about the present requirements of sea power and meeting them with realism rather than assumption. Defensive unmanned integration in expeditionary maritime security is no longer an experiment or a discretionary capability; it is a prerequisite for sustaining sea power in a contested world. Six Maritime is wholly committed to that effort.

Selected References & Further Reading

-Earl Hancock Ellis, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia (1921)

-Joseph H. Alexander, Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa -Craig C. Felker, Testing American Sea Power